Flight Date: April 30, 2017

We fly into the mountains.

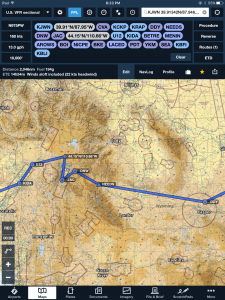

Departure: RAP

Destination: IDA (we planned for WYS, but switched to JAC and then to IDA)

Engine on: 10:00 AM MDT

Hobbs: 3.5

Gallons: 44.30

Distance: 393 nm

Day 2 was supposed to be the big day—and it delivered. We hoped to make aerial tours of Mount Rushmore, the Grand Teton, Yellowstone, and, importantly, cross the continental divide. We intended to finish with a terrestrial tour of Yellowstone before heading towards Idaho’s flatlands. In the end, nature and the FAA would change our plans. Nevertheless, besides being an interesting flight, this leg was also the one that provided the most learning opportunities. This post focuses on our flight to Togwotee pass, the place where we crossed the continental divide. Dealing with nature and the FAA is left for the next post.

Our planned departure time was 9:00 AM. We would have preferred an earlier departure, but the free shuttle from the hotel left either at 6:20 or 8:00 AM. 6:20 AM, following a great steak dinner in downtown Rapid City, was a little bit too much for us, so we signed up for 8:00 AM. A series of events, including a return to town in a courtesy car to pick up a forgotten mobile phone, delayed our departure until 10:00 AM. Frequent advice from those who fly the mountains is to be done with flying by noon; leaving at 10:00 we could be done in Jackson Hole by then, so taking advantage of clear blue skies and light winds, we charged west.

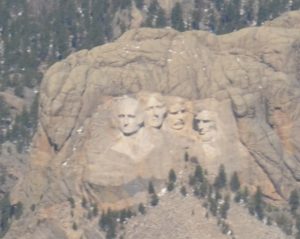

Our first detour took place 5 minutes after departure, as we slowed down and maneuvered around Mount Rushmore. The spectacular scene was a suitable preamble for what would follow.

Continuing west, we marveled at the long, desolate, Wyoming prairies. Flying over this area, similarly to flying over the South Dakota prairies, provides perspective on the west’s population density: cero. We asked for flight following from Denver Center, which provided comfort that if something happened, we would eventually be found. Flying without someone looking over you in this area is asking for a rescue to happen years later, when some hiker accidentally stumbles over the wreckage, and the corpses of the uninjured passengers are found some miles away, fallen from dehydration and cold temperatures. For example, this accident was discovered four years after it happened, near our route of flight. (As an extra precaution we carried a satellite GPS beacon, warm clothes, sleeping bags, and water.)

An hour of emptiness gave way to the mountains. They begin to show up, mildly, north of Casper. We continued cruising at 8,500 in mostly smooth air, contemplating mountain chains and peaks that surpassed our altitude. The mountains combined beautiful contours of snow, rock, and sparse vegetation, which unfortunately are hard to capture by amateur photographers. Nevertheless, they presage the quick change that follows the mountain pass we were about to take. From flat prairies to snowy forests in ten minutes!

After overflying Boysen reservoir, turbulence started to pickup somewhat. Up until then we had enjoyed a smooth ride with an occasional light chop. Now we were experiencing more of a continuous light chop. The emphasis is on light, though, as it never became uncomfortable.

That day, winds aloft 1,000 – 2,000 feet above the mountains for the Jackson Hole area were forecast to peak at about 20 kts. The magic number used by experienced mountain flyers as a limit for when to avoid mountain flying is 20 to 25 kts, so we felt confident this day would be a good opportunity to cross the continental divide. Our original plan was to fly to Cody and cross through Sylvan pass. This would place us immediately over Yellowstone, providing the second – after Mount Rushmore – “destination” scenic spot of the flight. However, weather forecasts for the area suggested that we would have more open skies towards the south. We therefore chose to cross through Togwotee pass. At 9,600 feet high, Togwotee pass was somewhat more challenging than Sylvan’s 8,500 feet. Thus, we planned to approach the pass area at 10,500, flying direct to NEEDS, an intersection close to Dubois (DUB), and climb to 11,500 or 12,500 if, as we got closer, we thought it necessary.

When I received my mountain flying endorsement a decade ago, I flew with an instructor over Tioga pass in California. The flight started in the bay area, and its destination was Mammoth Lakes airport, east of the Sierras. Tioga pass, only 300 feet higher than Togwotee, felt much more dramatic. Though on its west side terrain rises gradually, a steep 3,000 feet decline follows to the east. It is easy to imagine air flowing eastwardly and forming overpowering downdrafts, a lesson emphasized by my instructor back then. In preparation for the current flight, I had read reports on the perilous downdrafts faced by general aviation aircraft when crossing the Sangre de Cristo range in Colorado and New Mexico. Those ranges have steep slopes and aircraft flying direct –rather than choosing a pass—have encountered uncontrollable turbulence 4,000 and 5,000 ft above the peaks. Closer to our route, I had read Garrett Fisher’s account of flying near Togwotee pass (see here, and enjoy the much better pictures he has to offer of the area). For obvious reasons – after all, this flight was a celebration of life rather than the culmination of it – I was keen to avoid any such circumstance.

Mild winds meant the threat from rotors and other mechanical turbulence should have not been a problem. A scattered layer of none-rotor clouds, which had slowly turned into a broken ceiling, corroborated that assertion. Furthermore, as we advanced we discovered Togwotee pass is formed by relatively smooth-rising terrain on both sides, rising only 2,000 feet higher than the relatively flat terrain found a few miles out both east and west. Thus, when the time to cross came, smooth air, relatively smooth terrain, and excellent visibility meant we crossed at 10,500 without any issues.

A few miles before the crossing, Salt Lake City center had informed us that radar contact was lost, and that we were back to 1200 in the box. They added that we should be able to pick up Jackson tower in about 15 minutes. The feeling of being “on our own” at the most critical stage of the flight was not ideal. We immediately switched to Casper radio in an attempt to offer position reports. Establishing two-way communication took a few minutes and by the time we got a hold of Casper we were crossing the pass. In addition to providing a position report, we were able to provide a pilot report: “mostly smooth ride, broken ceiling estimated at 13,000, visibility more than 10 nm, and beautiful landscape.”

We had crossed the highest point in our journey, and the main dish in our sight-seeing flight was coming: the Grand Teton and Yellowstone’s Grand Prismatic.